Agricultural Technology

Machines

15. Feb. 2021

Upd. 22.11.2024

Manfred Goschler

Agriculture: Vimeo-free-videos from Pixabay

I’ve been to the Midwest before and noticed the abundance of agriculture in this region. You can drive for hours, surrounded by cornfields, in what is known as the “breadbasket of the nation.” In these fields, many machines from a particular manufacturer, headquartered in Moline, are prominent.

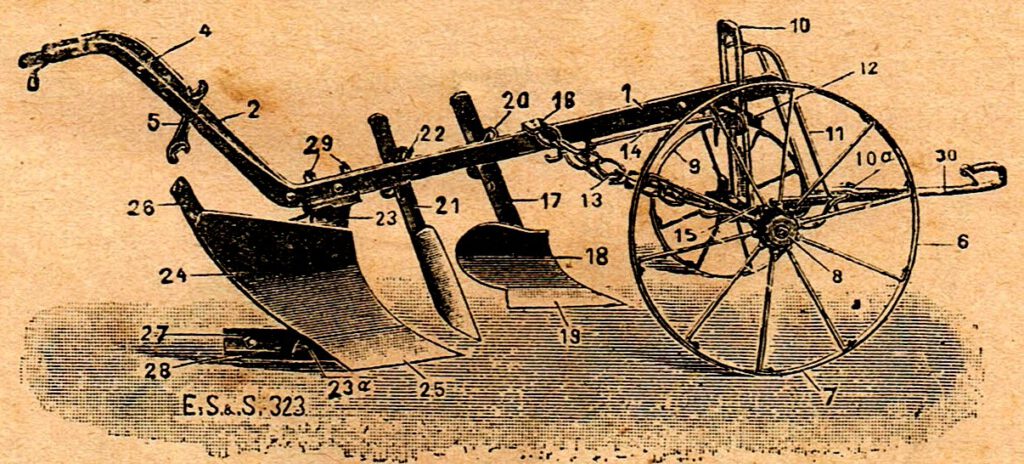

Farrier John Deere developed the first self-cleaning steel plow in 1837, laying the foundation for his now-famous company. Could this be a model for understanding the evolution of utility machines? The benefit seems obvious, as at the end of the process chain, these innovations address essential needs, such as feeding the population.

Let us first consider the underlying task. If John Deere had had access to the technological capabilities of our near future, something like a robot might have emerged to perform the job. Without these advanced tools, Deere developed a specialized device—a significant innovation for his time.

The plow is an agricultural tool designed to loosen and turn arable land. It can be understood as a simple machine that converts a pulling force into a pushing force. In the past, this pulling force came from draft animals harnessed to the plow. Today, tractors or other mechanized tugs perform this role. The mechanics of a plow redirect forces based on specific requirements to work the soil effectively.

Note: I assume that the development of a plow was highly complex compared to other devices, given the variances in soil conditions, areas of application, and corresponding force dynamics. Experts can certainly assess this more comprehensively.

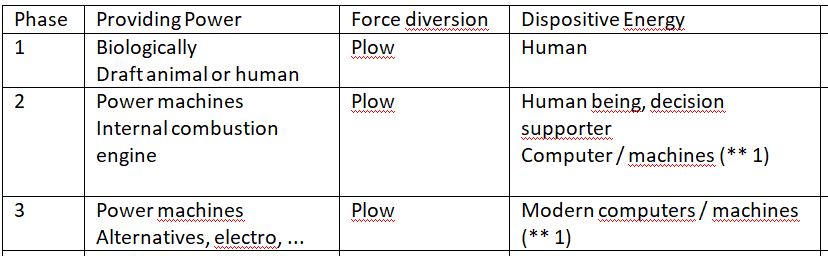

To simplify, one could say that, in addition to the power conversion provided by the plow, a power source (tractor) and control energies (human or machine operations) are essential to perform this task. The plow itself only fulfills one function within a broader task or process.

This very simplified representation highlights the growing degree of automation and machine utilization. In the final stage of this progression, machines operate independently, with humans no longer playing an active role. Alternatively, one might envision a robot or machine that integrates all necessary functions. However, for this discussion, these distinctions are secondary if we focus on the primary task.

This evolution presents a linguistic challenge as well—at least until all plows are fully automated. A farmer would no longer “plow” in the traditional sense; instead, they might oversee an autonomous machine and perhaps ride the tractor for leisure. Machines will also assume other roles, such as monitoring fields and crops, because in the future, they will surpass human capability in these tasks.

This brief exploration opens the door to deeper thoughts about the use of force, energy, or AI. Control programs can be decoupled and optimized through appropriate networks. What about other agricultural machines? A quick internet search using keywords like #AI or #MachineLearning connected with agriculture reveals the trajectory of these developments, which are driven by economic demands, environmental concerns, and a focus on sustainability.